Around the world, journalists, bloggers, medical workers, human rights defenders and all those who are raising concerns for the inadequate response to the Covid-19 pandemic are under attack. In an attempt to silence their dissenting voices, they are being accused of spreading false information, smeared, threatened, arrested, and physically attacked.*

Around the world, journalists, bloggers, medical workers, human rights defenders and all those who are raising concerns for the inadequate response to the Covid-19 pandemic are under attack. In an attempt to silence their dissenting voices, they are being accused of spreading false information, smeared, threatened, arrested, and physically attacked.*

From the beginning of the pandemic until October 2020, development banks earmarked a total US$95.2 billion for 770 Covid-19-related projects around the world, according to data gathered by the International Accountability Project, one of the members of the Coalition for Human Rights in Development. These banks have committed to respect and implement their social and environmental safeguards and to engage with all stakeholders, including journalists and civil society. However, they are failing to take actions to protect those who are criticising the emergency response, denouncing corruption scandals, and raising questions around transparency and accountability.

“UNHEALTHY SILENCE: DEVELOPMENT BANKS’ INACTION

ON RETALIATION DURING COVID-19″

Our Coalition members and press freedom organizations around the world are denouncing a growing backlash against media workers in the context of the pandemic and they are calling on development banks to take concrete actions to protect journalists.

In the sections below, you can find:

- The recording of the World Bank Civil Society Policy Forum Session “World Bank Funding and Freedom of the Press”, on October 8th, 2020.

- A list of recommendations to development banks.

- Resources for journalists at risk

- An overview of the press freedom situation and the banks Covid-19 response in Cambodia, Egypt, Mexico, Mongolia, Pakistan, Turkey and Zimbabwe.

- Read here the op-ed published for Devex: “No space for dissent — how development banks are supporting governments that silence journalists“

RECOMMENDATIONS

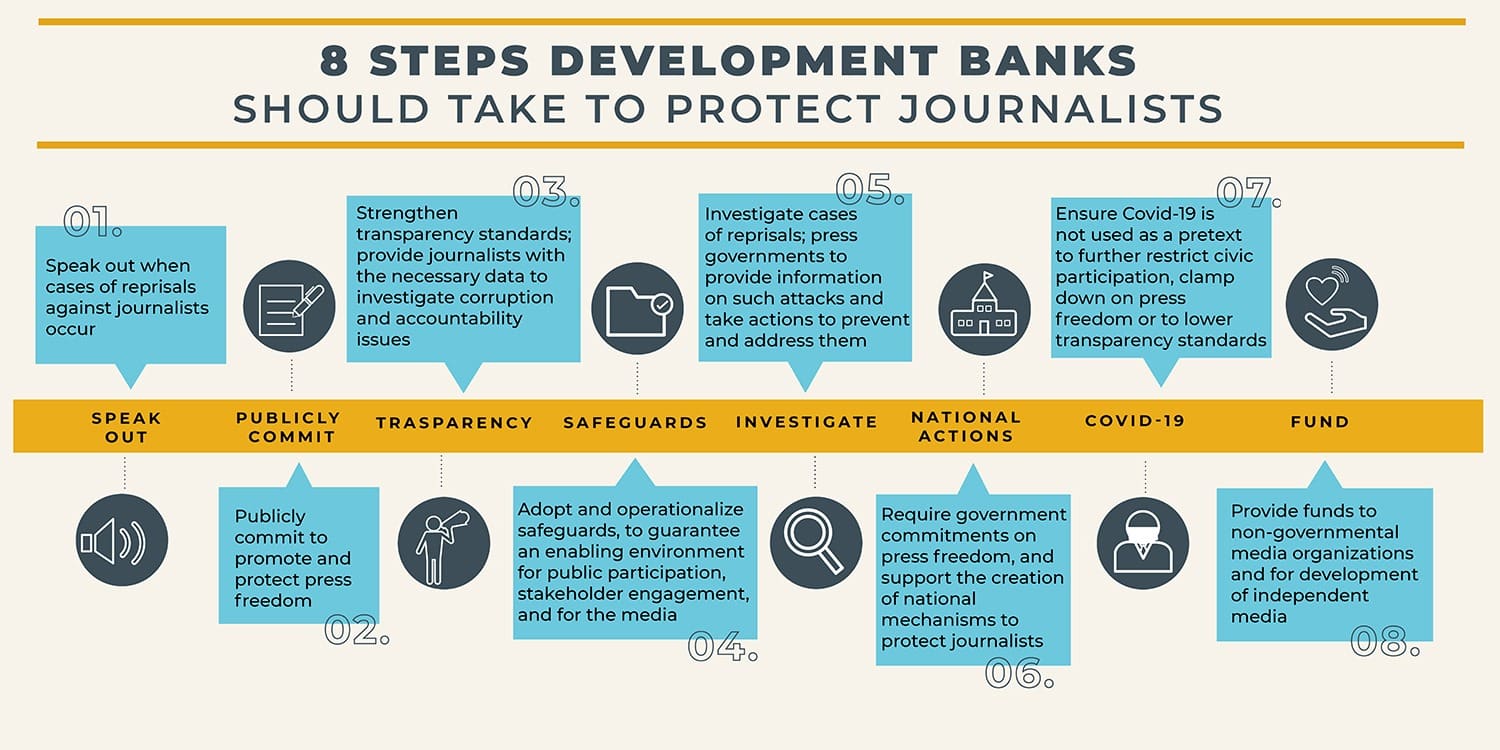

To protect journalists and support media freedom in the countries where they invest, development banks should:

- Speak out when cases of reprisals against journalists occur.

- Publicly commit to promote and protect press freedom.

- Adopt and operationalize safeguards, to guarantee an enabling environment for public participation, stakeholder engagement, and the media.

- Strengthen transparency and accountability standards, providing journalists and whistleblowers with the necessary data to investigate corruption, mismanagement, transparency, and accountability issues.

- Press governments to investigate cases of reprisals, to provide information on such attacks, and to take actions to prevent and address them.

- Require government commitments on press freedom, for example including such provisions in the loan agreements, and support the creation of national mechanisms to protect journalists.

- Ensure COVID-19 is not used as a pretext to further restrict civil participation, clamp down on media freedom, or to lower transparency standards.

- Provide funds to non-governmental media organizations and for development of independent media.

Download our infographic “Eight steps development banks should take to protect journalists” here.

RESOURCES FOR JOURNALISTS AT RISK

Here is a list of distress funds, grants and fellowships — including COVID-19 related funding & resources — compiled and updated on a bi-weekly basis by the IFEX Secretariat.

CAMBODIA

Financial support

- Asian Development Bank ($352 million)

- World Bank ($171 million)

- International Finance Corporation ($75 million)

Even prior to the pandemic, press freedom in Cambodia was already in decline, but the government has used Covid-19 as a pretext to further crack down on journalists. On 3rd March 2020, Prime Minister Hun Sen issued a statement warning that anyone spreading ‘fake news’ regarding the outbreak would be considered a terrorist and that the public should be active in combating the dissemination of this ‘fake news’.

The ‘fake news’ allegation has been used on several occasions to arrest Cambodian people for expressing concerns about Covid-19 on social media, limiting their ability as stakeholders in the projects funded by the banks as well as creating a chilling effect for others.

According to Human Rights Watch, “in the first weeks after the pandemic’s outbreak, the Cambodian authorities arrested over 30 people based on allegations that they had spread fake news about the virus in Cambodia. Among those arrested were opposition activists, a child, ordinary citizens speaking out on Facebook, and journalists.”

For example, on June 28 the publisher of the Khmer Nation newspaper, Ros Sokhet, was charged with incitement to provoke” serious chaos” for some social media posts. In one of the posts Sokhet had criticised the government for not offering solutions to people struggling to pay back bank loans.

A new state of emergency law was also hastily drafted and passed in April. The law contains broad and vague provisions, including unlimited surveillance of telecommunications, control of media and social media, as well as a concerning catch all provision – ‘putting in place other measures that are deemed appropriate or necessary to respond to the state of emergency’.

Soon afterwards, a new Law on Public Order which would grant the government provisions to regulate public spaces and public behaviour was drafted. This law has been widely criticised by civil society and UN experts as it risks violating the right to privacy, silencing free speech and criminalising peaceful assembly.

The government is also pushing through a sub-decree which would grant powers to control internet traffic. There are concerns that this could lead to limits on freedom of speech as the government will be able to block content, or deny access to online information. This legislation is being pushed through at a time when the pandemic makes it very difficult for the law to be properly reviewed through strong public consultation processes.

EGYPT

Financial support:

- European Investment Bank ($1758 million)

- European Bank for Reconstruction and Development ($525 million)

- International Finance Corporation ($75 million)

- World Bank ($100 million)

In Egypt, at least 9 health care workers and 10 journalists have been arrested since February in retaliation for criticising the government for its inadequate Covid-19 response, and for questioning how it spent the funds received.

Mohamed Mounir, a journalist and founder of the Front for the Defense of Journalists and Freedoms, was arrested in June and accused of spreading fake news, joining a terrorist organization and misusing social media, because he had written several posts asking the government how the Covid-19 funds were being spent. He died a month later, after contracting Covid-19 in jail, just a few days after being released on bail.

In March 2020, Egyptian authorities warned British-German journalist Ruth Michaelson to leave the country, as Egypt’s State Information Services (SIS) challenged her reporting of a study that suggested there were up to 19,000 cases in Egypt. At that time, the government was saying that there were less than 200 cases.

Also health care workers are being criminalised for speaking out and detained under vague charges of “spreading false news” and “terrorism”. As denounced by Amnesty International, in Egypt, “Health care workers are forced to make an impossible choice: risk their lives or face prison if they speak out”.

MEXICO

Financial support:

- World Bank ($1 billion)

- Inter-American Development Bank Invest ($337 million)

- Inter-American Development Bank ($300 million)

- European Investment Bank ($150 millon)

Prior to the pandemic, Mexico was already considered one of the most dangerous countries for journalists. Between March 12th and May 16th 2020 ARTICLE 19 documented approximately 120 attacks against the press, and 52 cases (43%), can be linked to coverage of the pandemic. National, federal and local authorities have been responsible for generating a polarized and threatening environment against the press, with direct attacks, stigmatization campaigns and denying information.

Coverage of the pandemic has been centralized via public conferences which are broadcast via social media, held by the President in the morning and the deputy Secretary for Health in the evening. However, only questions favorable to the government are answered, while those that question data provided by the government or are critical of its policies often result in stigmatizing comments and online retaliations by those in support of the current administration.

On April 1st, Denise Dresser, an academic and columnist, highlighted how the US was making projections on the pandemic and were preparing for thousands of deaths. She then asked why Mexico had not made such projections. The President replied saying “we are living in an age of vultures”. During the following weeks Dresser received social media many insulting and harassing comments on social media and the term « vultures » is now constantly used by authorities to criticize any journalist asking questions about Covid-19.

Disinformation and attacks against the press are widespread. In the state of Puebla, Governor Miguel Barbosa has been directly responsible for misinformation, saying that « the poor are immune to the virus » and that « the vaccine is a dish of turkey mole ». When questioned about these comments, the Governor has attacked the press and refused to reply to media that were criticizing his response to the pandemic. In Baja California, Governor Jaime Bonilla has been involved in a defamation campaign against several media groups. Any questioning or reporting of data which diverges from official propaganda is catalogued as « lies » and « an attack against this government ». Correspondingly, the states where more attacks against the press are being registered are also those with a higher number of Covid-19 cases.

MONGOLIA

Financial support

- Asian Development Bank ($174 million)

- International Finance Corporation ($142 million)

- Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank ($100 million)

- World Bank ($47.9 million)

On 29 April 2020, the Parliament of Mongolia rapidly passed a law on “prevention and fighting the Covid-19 pandemic and decreasing the negative impact to the society and the economy”. This law, along with an amended law on extreme situations and one on disaster prevention, have introduced provisions that risk censoring the media and reduce the space for civic engagement, online and offline.

The Covid-19 Law prohibits citizens from disseminating false information and obliges the media to deliver “true and objective information to the public from reliable sources” (para 14.2). Those breaching this law can face large fines, 240-720 hours of community-service hours, or a restriction on their right to travel. Para 10.4.13 of the newly amended Law on Disaster Prevention also protects dissemination of ‘fake news’ through traditional media and on social networks.

Mongolian press freedom and anti-corruption activists are concerned that the law does not define what constitutes false information. The fears are justified as a former – weaker – law under which defamation charges were previously brought saw over 100 journalists charged.

According to civil society in Mongolia, the new and newly amended laws and criminal defamation provisions restrict the critical and investigative journalism reporting necessary at this time. For example in July, Parliamentary Speaker, Mr. Zandanshatar invited around 30 journalists from print, broadcast and online media outlets and suggested they not report and disseminate information on the newly amended Constitution. Although not directly related to COVID, this is demonstrative of the Mongolian government’s approach to dealing with the press and goes some way to demonstrate why journalists might self-censor their work.

Throughout lockdown restrictions in Mongolia, the police has been responsible for preventing people from traveling. However, after a young citizen from Khuvsgul province posted on Facebook that police officers were being bribed during the quarantine by people wanting to travel from the provinces to the capital, rather than sparking an investigation, he was fined MNT 550,000 for supposedly distributing false information.

PAKISTAN

Financial support:

- Asian Development Bank ($1,802 million);

- Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank ($750 million)

- World Bank ($720 million)

In Pakistan, even prior to the pandemic journalists were facing stigmatization campaigns, threats, intimidation, and physical attacks, but the situation has now worsened as the government has been using the pandemic as a pretext to further restrict freedom of expression. Moreover, readership and circulation of newspapers are rapidly declining and salaries are being reduced, but no relief package was awarded to the media.

Some attacks against journalists were directly related to their reporting on the pandemic. Two TV reporters, Saeed Ali Achakzai and Abdul Mateen Achakzai, were held three days by a paramilitary force and tortured, after reporting on a public protest against the poor facilities at a quarantine centre in Balochistan. There are other cases involving journalists, including citizen journalists, looking to highlight shortcomings of the government Covid-19 support programme have faced restrictions and there have also been allegations of beatings and torture by security forces in cases where journalists do attempt to cover the issue.

The government is also trying to step up online “regulation,” with the pretext of controlling misinformation. In February 2020, the government approved rules to regulate social media. The Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) has also introduced a new set of restrictive directives for reporting on Covid-19. Press freedom organizations, such as Article 19, have also expressed their concern for the proposal of the Citizens Protection (against Online Harms) Rules. As reported by Article 19, “the Rules grant a government agency extensive powers to order the blocking or removal of vaguely defined content in the absence of any meaningful safeguards in violation of international standards on freedom of expression. They also provide for obligations to filter content and to disclose user data at the request of the government in breach of international standards on privacy.

TURKEY

Financial support

- Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank ($874 million)

- World Bank ($760 million)

- European Bank for Reconstruction and Development ($594 million)

- International Finance Corporation ($125 million)

The Covid-19 outbreak has given authorities an additional excuse to target the media, adding a new layer to the crackdown on media freedom in Turkey. Journalists have been targeted across the country under the guise of combating misinformation. Turkey has seen journalists facing criminal investigation and detention for reporting or even tweeting on Covid-19.

In a bid to take further control over social media, Turkey’s parliament has now passed a controversial new law granting it sweeping powers over social media companies. Under the new law, platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram etc. will be forced to block or fully remove content at the request of the government. Noncompliance would result in fines and the restriction of bandwidth to slow or block traffic to their site. There are also concerns that the law could mean social media companies handing over personal details of users to the Turkish government.

On the 4th of March editor-in-chief of a local news website in Antalya and the same site’s senior editors – İdris Özyol and Ebru Küçükaydın – were detained, questioned and then released over a news report concerning Covid-19. Their news report is now no longer available online.

İsmet Çiğit, the editor-in-chief of local newspaper SES Kocaeli, was detained on 18th March following the publication of an article on the SES Kocaeli website about the death of two people in a local hospital from Covid-19. The newspaper’s executive responsible for the website, Güngör Aslan, was summoned by the authorities the next day. Both were questioned about their sources in the hospital, and felt pressure to stop their reporting on the issue. They were both released after giving a statement to the prosecutor and stating that they will no longer report on Covid-19.

Former Halk TV editor-in-chief, Hakan Aygün, was remanded in prison on 4th April because of his social media posts on Facebook and Twitter criticizing Turkey’s President Erdoğan’s sharing of a bank account number for donations from the public to help with the pandemic. His play on words – changing the word IBAN to IMAN meaning “religious belief – caused him to be charged under articles prohibiting “inciting the public to enmity and hatred” and “insulting the religious beliefs of a section of society”. His case is ongoing.

On 30th April Fox TV presenter, Fatih Portakal, was indicted for damaging the reputation of the banks following a tweet on 6th April in which he compared the Covid-19 Aid appeal to additional taxes collected during the war of independence at the end of the first world war. A complaint by the Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency (BDDK) for the tweet led to investigations for “insulting the President” and for “deliberately damaging the reputation” of banks. Portakal’s tweet was blocked by court order on 8th April before the indictment on 30th April.

Three broadcasts of the news programme Portakal presents were found to have incited enmity and hatred during broadcasts. The regulatory body, the Radio and Television High Council (RTÜK) imposed the highest penalty on FOX TV by stopping the broadcast of the programme three times.

Journalist and human rights defender Nurcan Baysal has also been interrogated by the police. On 30th and 31st March she was interrogated about her recent social media posts and two recent articles, commenting on the precautions taken by the government against Covid-19 and their implementation in Diyarbakir and other Kurdish cities, as well as the measures being taken in Diyarbakir’s prisons. She was questioned about her motives for posting on Twitter which amounted to a “threat to incitement to fear and panic among the public”, according to the record of her statement issued by the police. If indicted, she may be charged with “provoking the public to hatred and hostility”.

ZIMBABWE

Financial support

- World Bank – ($49.6 million);

- African Development Bank – (10,000,000 UAC, approximately equivalent to $14 million)

The Zimbabwean authorities have taken actions against independent media outlets and arrested reporters who were scrutinizing and/or criticising the Covid-19 response.

On 20 July 2020, human rights defender and journalist Hopewell Chin’ono was arbitrarily arrested at his home in Harare and charged with ‘incitement to commit public violence’. He remained in jail for 45 days and he was finally released on bail on 2 September. As reported by Front Line Defenders, “The charges against Hopewell Chin’ono are in relation to posts he made on social media, calling on citizens to participate in the anti-corruption demonstrations that took place on 31 July around the country. Authorities and the investigating officer on the case claimed that the posts incited people to participate in gatherings that would promote a breach of the peace, and that the aim of these demonstrations was to overthrow the Government of Zimbabwe. The aim of the protests however, was to denounce corruption, mismanagement of the economic crisis and the lack of reforms by the government. The defender believes he has been targeted in reprisal for his investigation and reporting on the alleged case of government corruption involving Covid-19 medical supplies in June 2020. The Minister was dismissed from his role and arrested as a result of the scandal.

Mduduzi Mathuthu, another Zimbabwean journalist who reported on the same corruption scandal, is still in hiding as he fears for his life. On 30 July, security forces raided his house and – failing to find him – arrested his sister and three of his nephews. Mduduzi is the founder and editor of Zim Live, a news website that exposed massive corruption and gross mismanagement of funds meant for the COVID-19 response in Zimbabwe. According to MISA Zimbabwe, one nephew was even tortured by alleged security agents. Two other Zimbabwean journalists, Frank Chikowore and Samuel Takawira, were also arrested for offences related to violating the Covid-19 rules and acquitted in September.

* For further information, please check out the online tracker developed by Reporters Without Borders (Tracker 19), which is monitoring the pandemic’s impacts on journalism and documenting attacks against press freedom worldwide.